|

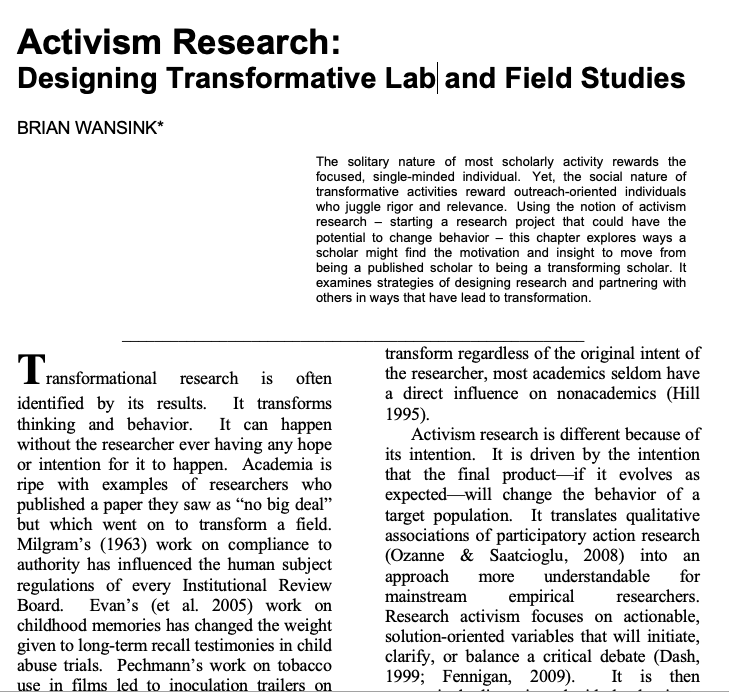

Note: This is from an earlier 2018 blog post at BrianWansink.com Tomorrow I retire from Cornell; it will be two days after I turned 59. My Mom and Dad both retired from their union jobs within days of their birthdays, and I never remember them saying much about their jobs after that day. Someone else took my Dad’s place on the production line, and someone else took my Mom’s place filing papers. But academia is different. It’s one profession you never really have to retire from. A lot of us have a lot to say, and we’re passionate about saying it even when we’re officially through with our job. Many academics imagine themselves retiring in their early 70s, and even then maybe only transitioning to half-time until they befuddle us by changing the lock on our office. Even retirement parties are somewhat pro forma. If you feel you have a calling for academia, you don’t feel any different the day after you retire. I just had my retirement party last month and it seemed like a birthday party, except that people gave speeches and gave me a cherry wood captain’s chair with the Cornell logo on the front and a touching engraving on it. In 30 years of academia, I only once went to a retirement party that didn’t just seem like was another birthday party for the person who was retiring but who was going to be at work again tomorrow at they exact same time they always are. But seeing this one retirement party had a striking effect on me. It happened about 15 years ago, and I was asked to be one of two faculty speakers at the annual Spring meeting of the university’s Business Advisory Committee; it was also doubling as a retirement party for an amazing man. He was one of the most notable economists at the University. He occupied a rare niche at the intersection of economics, real estate, finance, and law. He was widely published, widely influential, and even his economist colleagues spoke of him in awe. This year was his retirement year, and his speech would perhaps be his Last Waltz in front of a group like this. We got to know each other throughout the day and up through the closing reception. On the rainy long ride home, we sat next to each other in the back of the dark and quiet chartered bus. I asked him which of his many accomplishments he most proud of, and which had the most impact. At one point, however, I asked a question that was not met with the same warmth and candor. I asked, "In light of all of the remarkable things you’ve accomplished so far in your career, what’s your biggest professional regret?" Silence. Then he eventually said, "I don’t have any regrets. If I had to do it again, I would do everything pretty much the same way." After another long pause he then recanted a bit and said something like this:

I said, “Would it be easier for people to see your big picture if you were to write a book that pulled all of this together? That way, everything would be in one place and you could connect all the dots.” He chuckled and immediately dismissed this, “I don’t know about marketing, but in economics they don’t reward books.” After 45 years of research, here was a great man who was retiring with one needless regret. Yet, what he let get in his way was how he would be rewarded or whether a colleague might think he was simplifying his research for the amateurs. It seemed to me that writing a book would have been a potentially transforming project. The metaphor that is relevant for us is not the metaphor of writing a book. The appropriate metaphor is for anyproject that might ratchet up our level of impact. It is any project that may not be rewarded with the respect of the “professor next door,” but it is that which we think is critically important. In fact, it might be even be actively derided. That’s what happened to a number of metaphorical books. It happened to Carl Sagan’s award-winning Cosmos series on PBS, to Gary Becker’s famous Business Week columns, to Steven Levitt’s “Freakonomics” to Paul Krugman’s New York Times columns, to Richard Posner’s Federal Judge appointment, and to Stephen Ambrose’s National World War II Museum. The notion of an "unwritten book" can be a powerful and useful metaphor for us. For many of us, there is at least one metaphorical book that would take our ideas to a new level of influence. It might be starting a website and blog, presenting research in front of a House subcommittee in order to propose a law, making class modules for science teachers, writing a review article in a related field, starting a company, or starting a new class and turning the notes into an engaging distance-learning course. What’s interesting is that most of these “unwritten books” probably wouldn’t have to wait. They were something that could have been started much earlier if we would have removed our self-limiting barriers. --- I remember another topic that I discussed with that eminent economics professor on the long ride back home. It was how quickly he said that his research years had passed. He said that after he graduated with his PhD, he blinked and had tenure; he blinked again and he had an endowed chair; he blinked again and he was riding with me on what he called “his retirement bus.” The idea of starting a career of activism research when “the time is right” could disappear in a blink of an eye. Time to start the next chapter.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

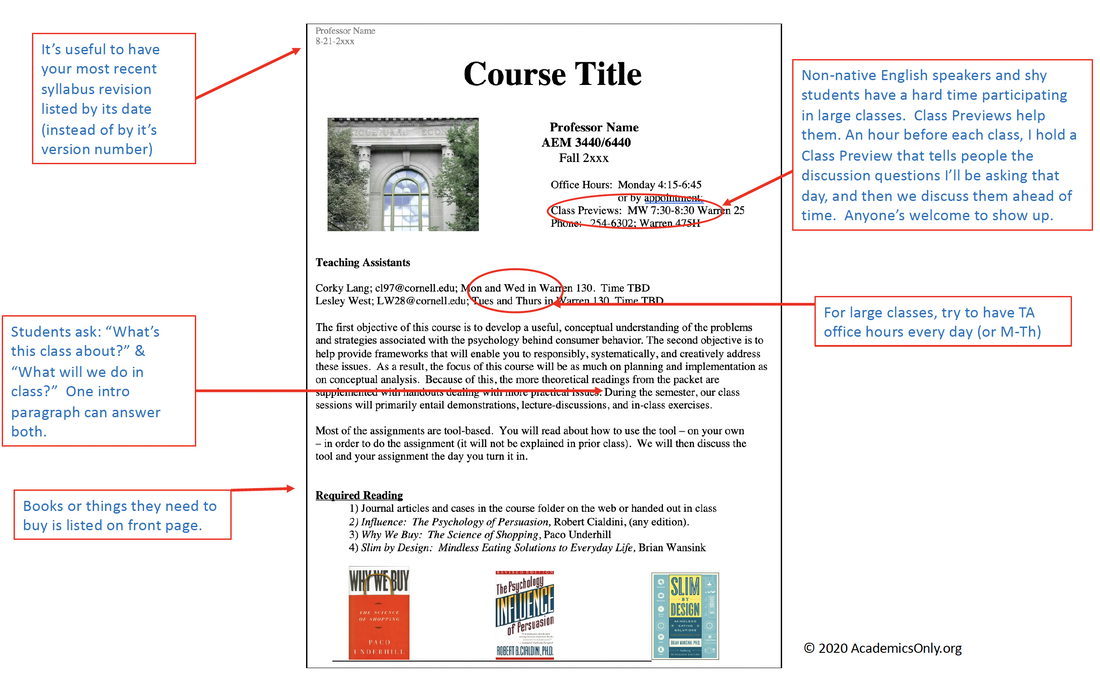

Welcome...Tips for PhDs is a how-to community that helps us share our best practices as PhD students, new professors, and independent scholars.

Helpful tools and tips on how to graduate, get tenure, teach better, publish more, and have a super rewarding career.

Relevant Posts

All

Some Older PostsArchives

April 2024

|

||||||||||

Share Your Insights and IdeasWhat have you created or found that's been useful and could be helpful for other PhD students, new professors, or independent scholars?

Send an email to [email protected] if you have something you think would be useful to share with others on this website, or if you have ideas on how to make this more useful to you or your students. |

Stay in touch |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed