|

On a late afternoon about 20 years ago, I stepped into a slow elevator with my college’s most productive, famous, and taciturn senior professor. After 10 seconds of silence, I asked, “Did you publish anything yet today?” He stared at me for about 4 seconds and said, “The day’s not over.” Cool . . . very Clint Eastwood-like.

Most of us have some super-productive days and we have some bad days, but most lie in-between. If we could figure out what leads to great days, we might be able to trigger more of them in our life. For instance, if you want to write a whole lot, there might be a way to set up your day so that this happens with a surprising amount of ease. Think of the most recent “great day” you had. What made it great, and how did it start? For about 20 years, every time somebody told me they had a great day, I’d ask “What made it great? How did it start out? About 50% of the time its greatness had to do with an external “good news” event like something great happening at work, great news from their kids or spouse, a nice surprise, or nice call or email from a grateful person or an old friend. The other 50% of the time, the reason for “greatness” was more “internal.” They had a super productive day, they finished a project or a bunch of errands, or they had a breakthrough solution to a problem or something they should do. External successes are easy to celebrate with our friends. Internal successes are more unpredictable. What made today a great day and what sabotaged yesterday? When people had great days, one reoccurring feature was that they started off great. There was no delay between when they got out of bed and when they Unleashed the Greatness. People said things like, “I just got started and seemed to get everything done,” or “I finished up this one thing and then just kept going.” One of the most productive authors I've known said that got up six days a week at 6:30 and wrote from 7:00 to 9:00 without interruption. Then he kissed his wife good-bye and drove into school and worked there. When I asked how long he had done that he said, “Forever.” About a year ago, I started toying with the idea that "Your first two hours set the tone for the whole day." Think of your last mediocre day. Did it start out mediocre? That would also be consistent with this notion. We can’t trigger every day to be great, but maybe we have more control than we think. If we focus on making our first two hours great, it might set the tone for the rest of the day. What we need to decide is what we can we do in those first two hours after waking that would trigger an amazing day and what would sabotage it and make it mediocre. For me, it seems writing, exercise, prayer, or meditation are the good triggers, and it seems answering emails, reading the news, or surfing are the saboteurs. Here’s to you having lots of amazing days. One’s where you can channel your best Clint Eastwood impression and say, “The day’s not over.”

0 Comments

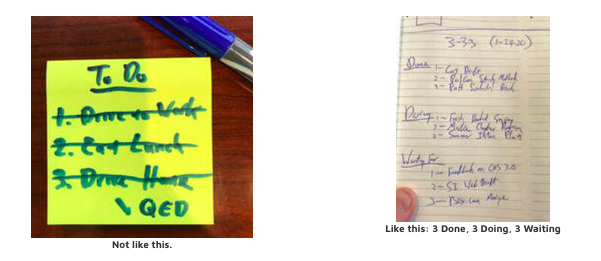

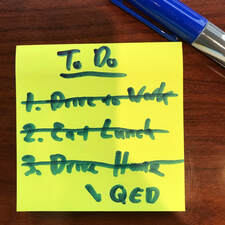

There are 100 things on your mental To-Do list. There are daily duties (like email and office time) and pre-scheduled stuff (like classes and committee meetings). But what still remains at the end of the day are the things that are easy to put off because they don’t have hard or immediate deadlines – things like writing an intro to a paper, submitting an IRB proposal, drafting a grant, completing some analysis tables, and so on. At the end of the year, having finished all of these might be what makes the difference between an exceptional year and another “OK” one.

But these projects are also the easiest things to put off or to only push ahead 1 inch each week. If you push 100 projects ahead 1 inch each week, you’ve made 100 inches of progress at the end of the week, but your desk is still full and you’re feeling frustratingly resigned to always be behind. This is an incremental approach. A different approach would be to push a 50-inch project ahead until it is finished and falls off the desk; then you could push a 40-inch project ahead until it falls off; and then you can spend the last of your time and energy pushing a small 10-inch project off your desk. This is the “push-it-off-the-desk” approach. Both approaches take 100-inches of work. However, the “push-it-off-the-desk” approach changes how you think and feel. You still have 97 things left to do, but you can see you made tangible progress. For about 12 years, I tried a number of different systems to do this – to finish up what was most important for the week. Each of them eventually ended up being too complicated or too constraining for me to stick with. Eventually I stopped looking for a magic system. Instead, at the end of every week, I simply listed the projects or project pieces I was most grateful to have totally finished. Super simple. It kept me focused on finishing things, and it gave me a specific direction for next week (the next things to finish). It’s since evolved into something I call a “3-3-3 Weekly Recap.” Here’s how a 3-3-3 Weekly Recap works. Every Friday I write down the 3 biggest things I finished that week (“Done”), the 3 things I want to finish next week (“Doing”), and 3 things I’m waiting for (“Waiting for”). This ends up being a record of what I did that week, a plan for what to focus on next week, and a reminder of what I need to follow up on. It helps keep me accountable to myself, and it keeps me focused on finishing 3 big things instead of 100 little things. Here’s an example of one that’s been scribbled in a notebook at the end of last week: Even though you’d be writing this just for yourself, it might improve your game. It focuses you for the week, it gives you a plan for next week, and it prompts you to follow-up on things you kind of forgot you were waiting for. Sometimes I do it in a notebook and sometimes I type it and send it to myself as an email. It doesn’t matter the form it’s in or if you ever look back at it (I don’t), it still works. I’ve shared this with people in academia, business, and government. Although it works for most people who try it, it works best for academics who manage their own time and for managers who are supervising others. They say it helps to keep the focus on moving forward instead of either simply drifting through the details of the day or being thrown off course by a new gust of wind. If you work with PhD students or Postdocs, it could help them develop a “Finish it up” mentality, instead of a “Polish this for 3 years until it's perfect” mentality. It’s also useful as a starting point for 1-on-1 weekly meetings. If they get in the habit of emailing their 3-3-3 Recap to you each Friday, you can share any feedback and perhaps help speed up whatever it is they are waiting for. Especially if it’s something on your desk. Ouch. Good luck in pushing 3 To-Dos off your desk and getting things done. I hope you find this helps. |

Welcome...Tips for PhDs is a how-to community that helps us share our best practices as PhD students, new professors, and independent scholars.

Helpful tools and tips on how to graduate, get tenure, teach better, publish more, and have a super rewarding career.

Relevant Posts

All

Some Older PostsArchives

April 2024

|

Share Your Insights and IdeasWhat have you created or found that's been useful and could be helpful for other PhD students, new professors, or independent scholars?

Send an email to [email protected] if you have something you think would be useful to share with others on this website, or if you have ideas on how to make this more useful to you or your students. |

Stay in touch |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed