How do I Find a Thesis Advisor?

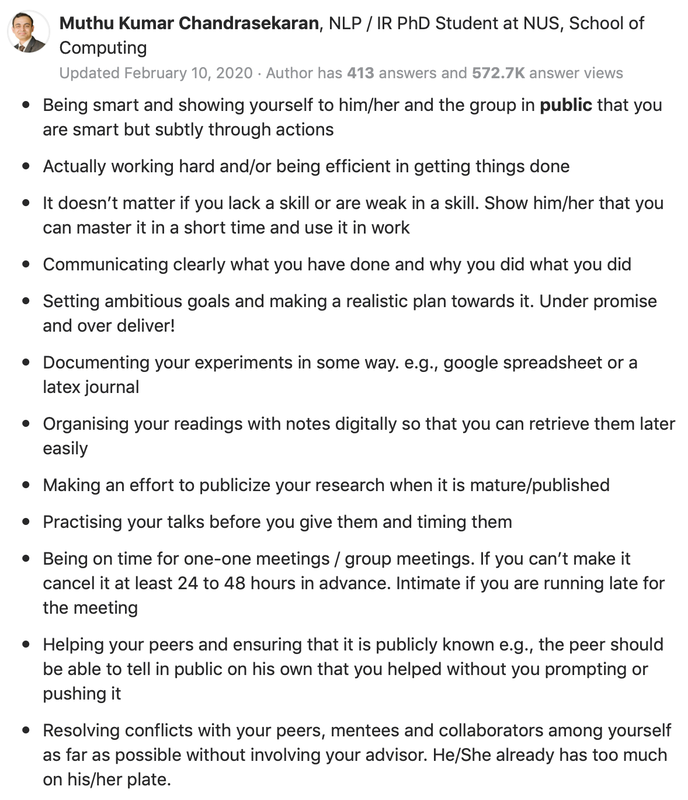

Finding Your Advisor

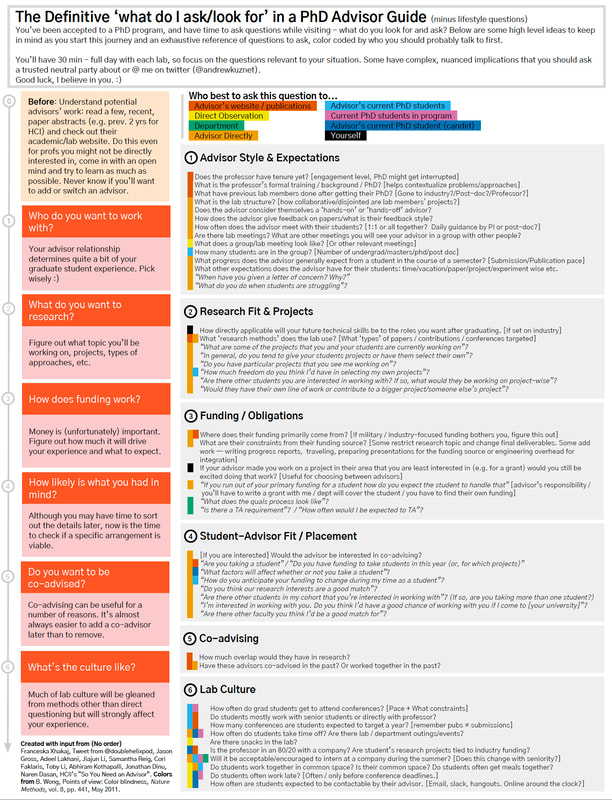

Great pdf for STEM, and 80% is relevant for social sciences and humanities |

|

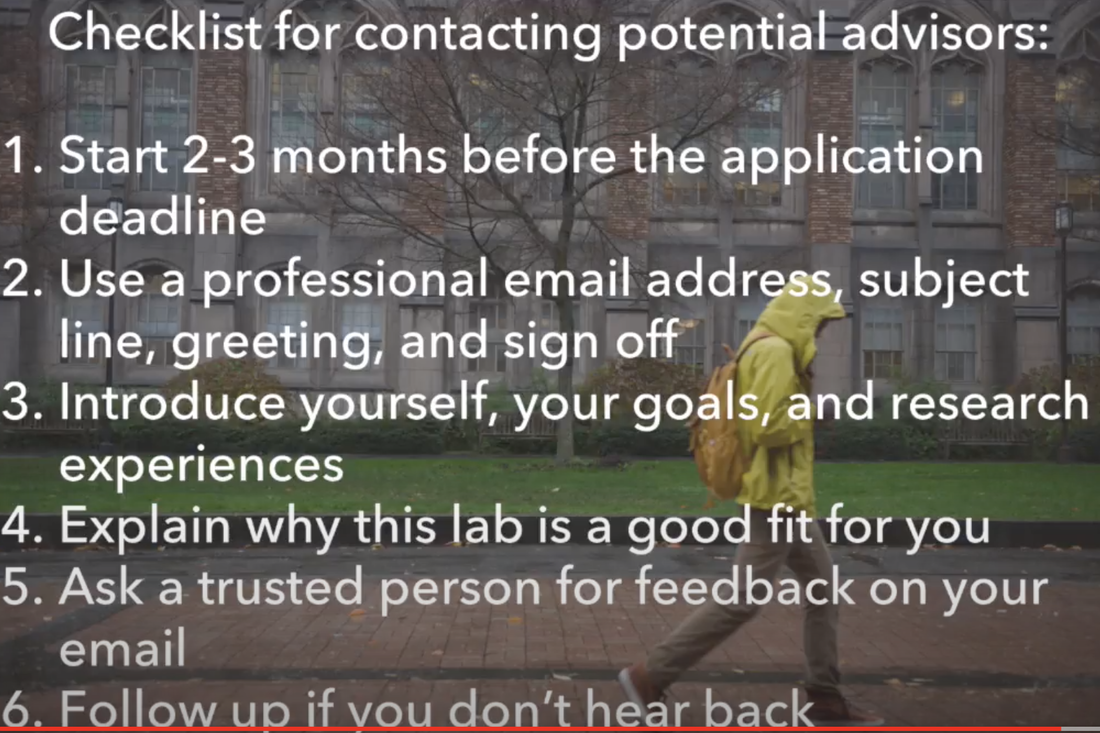

How to Impress Your Advisor (and not annoy them)

How to impress your advisor |

Top ways to annoy your advisor1. Disappear

2. Mess around with dates and deadlines 3. Ask for help before trying to solve it yourself 4. Leave our meetings without knowing what to do next 5. Talk to other academics without discussing with them first 10 Nonobvious tips for PhD Advisor successTen types of PhD supervisor relationships |

How to Choose the Perfect Advisor and Thesis Committee:

Two Case Studies

|

A former Summer Intern was over Saturday night with her PhD-student husband and the issue of choosing the best advisor came up between dinner and a game of Pandemic. The topic of choosing an advisor most famous person in the department or the one who likes you most was the issue. It's a very important and also timeless question.

|

Typically, the gravitational pull for choosing an advisor is strongest for those with big reputations. Picking the hottest, most famous person in a field is one way to pick an adviser. After all what could go wrong?

Case Study #1. A number of years ago at a different university, I had a good friend who was starting her PhD in environmental engineering over a second time. Her first go-around had been after she chose the “most famous” person in her field at the most famous school in her field as her adviser. She hated it, hated the school, and ended up leaving with what she called “a consolation Master’s degree.” She said her famous adviser had never around, never cared about her, never thought she was smart enough or working hard enough, never liked her ideas, and that he played favorites with the more advanced students.

Case Study #2. I too had originally chosen the “most famous” person in my field, and things didn’t work out. As a 3rd year PhD student I thought I was going on the job market. Instead I was told my funding was being eliminated, and that I had 4 months to find a new dissertation adviser, a new dissertation topic, and to defend that topic, or I would be asked to leave the program (probably without the consolation Masters).

One conversation rescued me from having to start a PhD a second time a different school. Three shell-shocked days after being blind-sided, I was talking to a friend who was a professor in the medical school. I told him what had happened and about my confusion. He said, “If I knew you were going through this, I would have told you what I tell my graduate students. ‘When it comes to picking a thesis committee, you pick your best friend to be your thesis adviser, your favorite uncle to be one committee member, and your favorite cousin to be your other.’”

This is a radically different approach than what I had used, what the environmental engineer had used, and what Jack was using. The advice was to “Pick your best friend to be your advisor.” Not “the most famous” person in the department. Not even the person whose research interests are most like yours. Pick the person who likes and believes in you and your best interests. You might not be as “hot” when you graduate, but you might be a lot more likely to graduate in the first place.

I’ve been thinking about this because this past weekend I looked up “Jack” to see if he wanted to take a dissertation break come over and meet some of my grad students. On his department’s website, I noticed that he was about the only 3rd year student who wasn’t a formal part of any of the research groups in the Lab of his “famous advisor.” That was like me. Fortunately, I was given a second chance.

Picking a star-spangled dissertation or thesis committee that you think will make you “hot” on the job market is a great strategy for Super-Duperstars. For the other 90% of us, we should pick one that will help us graduate.

Case Study #1. A number of years ago at a different university, I had a good friend who was starting her PhD in environmental engineering over a second time. Her first go-around had been after she chose the “most famous” person in her field at the most famous school in her field as her adviser. She hated it, hated the school, and ended up leaving with what she called “a consolation Master’s degree.” She said her famous adviser had never around, never cared about her, never thought she was smart enough or working hard enough, never liked her ideas, and that he played favorites with the more advanced students.

Case Study #2. I too had originally chosen the “most famous” person in my field, and things didn’t work out. As a 3rd year PhD student I thought I was going on the job market. Instead I was told my funding was being eliminated, and that I had 4 months to find a new dissertation adviser, a new dissertation topic, and to defend that topic, or I would be asked to leave the program (probably without the consolation Masters).

One conversation rescued me from having to start a PhD a second time a different school. Three shell-shocked days after being blind-sided, I was talking to a friend who was a professor in the medical school. I told him what had happened and about my confusion. He said, “If I knew you were going through this, I would have told you what I tell my graduate students. ‘When it comes to picking a thesis committee, you pick your best friend to be your thesis adviser, your favorite uncle to be one committee member, and your favorite cousin to be your other.’”

This is a radically different approach than what I had used, what the environmental engineer had used, and what Jack was using. The advice was to “Pick your best friend to be your advisor.” Not “the most famous” person in the department. Not even the person whose research interests are most like yours. Pick the person who likes and believes in you and your best interests. You might not be as “hot” when you graduate, but you might be a lot more likely to graduate in the first place.

I’ve been thinking about this because this past weekend I looked up “Jack” to see if he wanted to take a dissertation break come over and meet some of my grad students. On his department’s website, I noticed that he was about the only 3rd year student who wasn’t a formal part of any of the research groups in the Lab of his “famous advisor.” That was like me. Fortunately, I was given a second chance.

Picking a star-spangled dissertation or thesis committee that you think will make you “hot” on the job market is a great strategy for Super-Duperstars. For the other 90% of us, we should pick one that will help us graduate.