|

On a late afternoon about 20 years ago, I stepped into a slow elevator with my college’s most productive, famous, and taciturn senior professor. After 10 seconds of silence, I asked, “Did you publish anything yet today?” He stared at me for about 4 seconds and said, “The day’s not over.” Cool . . . very Clint Eastwood-like.

Most of us have some super-productive days and we have some bad days, but most lie in-between. If we could figure out what leads to great days, we might be able to trigger more of them in our life. For instance, if you want to write a whole lot, there might be a way to set up your day so that this happens with a surprising amount of ease. Think of the most recent “great day” you had. What made it great, and how did it start? For about 20 years, every time somebody told me they had a great day, I’d ask “What made it great? How did it start out? About 50% of the time its greatness had to do with an external “good news” event like something great happening at work, great news from their kids or spouse, a nice surprise, or nice call or email from a grateful person or an old friend. The other 50% of the time, the reason for “greatness” was more “internal.” They had a super productive day, they finished a project or a bunch of errands, or they had a breakthrough solution to a problem or something they should do. External successes are easy to celebrate with our friends. Internal successes are more unpredictable. What made today a great day and what sabotaged yesterday? When people had great days, one reoccurring feature was that they started off great. There was no delay between when they got out of bed and when they Unleashed the Greatness. People said things like, “I just got started and seemed to get everything done,” or “I finished up this one thing and then just kept going.” One of the most productive authors I've known said that got up six days a week at 6:30 and wrote from 7:00 to 9:00 without interruption. Then he kissed his wife good-bye and drove into school and worked there. When I asked how long he had done that he said, “Forever.” About a year ago, I started toying with the idea that "Your first two hours set the tone for the whole day." Think of your last mediocre day. Did it start out mediocre? That would also be consistent with this notion. We can’t trigger every day to be great, but maybe we have more control than we think. If we focus on making our first two hours great, it might set the tone for the rest of the day. What we need to decide is what we can we do in those first two hours after waking that would trigger an amazing day and what would sabotage it and make it mediocre. For me, it seems writing, exercise, prayer, or meditation are the good triggers, and it seems answering emails, reading the news, or surfing are the saboteurs. Here’s to you having lots of amazing days. One’s where you can channel your best Clint Eastwood impression and say, “The day’s not over.”

0 Comments

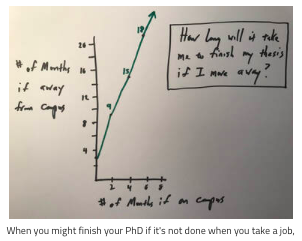

Some people love graduate school, but most of us want to finish it up and get started with our real lives. About a couple years ago I met a nice guy from Utah who was finishing his thesis at a university about 5 hours away. He had just moved here to take a job. After only two weeks, he was totally immersed in his new job, and I asked him if he was concerned about being able to finish up his thesis. He said, "Oh, no, not at all. My university's only 5 hours away, and I've only got a couple months of work left on it." The idea of starting a new life or a new job a few months early – say, before we’ve completed our dissertation – sounds pretty good. After all, lots of people Zoom and Skype from home, so it should be a snap to web-commute back to the university and finish up our dissertation away from the anxieties of campus. For instance, you could now start your new gig (maybe as a professor) in June instead of August. Your plan would be to move, get settled, wrap up the dissertation, and get two months of a tempting new salary. When I was a PhD student, someone told me that if you want to know how long it will take to finish your dissertation if you move away, you use a simple formula. You take your best guess of how long you think it will take to finish, then you triple it and add three months. So if you think you have 2 months left on your dissertation, and you move away in June, you won’t be finished until following March – in 9 months instead of 2 months (2 months x 3 + 3 months = 9 months). This is a rough rule-of-thumb, that varies across schools, departments, and people. Still, when I heard this, I wasn’t going to take any chances. My apartment lease with my two roommates was up, so I spent the last two months crashing at the apartments of different friends so I could wrap it my dissertation and graduate before I move away to start my Asst Prof gig.

What happens when you move is not only that it takes time to get resettled and you no longer have the support structure of your PhD program (and the “in sight & in mind” attention of your committee), but you also don’t feel the urgency to finish. You’re settling into a new role, and everybody's happy to have you around. You start to put off the uncomfortable pressure of you incomplete dissertation because it feels so much better to be treated as an an adult over here than as a sniffling child over there. But in a few months when your new department chair asks whether you’re through with your dissertation, it’s going to be awkward to answer. You might not have the option of completing a dissertation on campus, but if you can, it’s worth sleeping on couches until it’s done. ****************************************** The Rest of the Story: Four months after meeting the guy from Utah, I ran in to him again at the same boardgame cafe where we had originally met. He was very excited about having moved, and he was very excited about his new job. What's notable was that he never mentioned anything about his dissertation, how it was going, or whether it was finished. His dissertation had been an enthusiastic 80% of our conversation during the first time we met. Sine he never mentioned it, I wonder if he hadn't made the progress he had expected to make. |

Welcome...Tips for PhDs is a how-to community that helps us share our best practices as PhD students, new professors, and independent scholars.

Helpful tools and tips on how to graduate, get tenure, teach better, publish more, and have a super rewarding career.

Relevant Posts

All

Some Older PostsArchives

April 2024

|

Share Your Insights and IdeasWhat have you created or found that's been useful and could be helpful for other PhD students, new professors, or independent scholars?

Send an email to [email protected] if you have something you think would be useful to share with others on this website, or if you have ideas on how to make this more useful to you or your students. |

Stay in touch |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed