|

Some scholars are truly amazing and heroic. They’re self-made, and their career’s been flawlessly filled with perfect decisions and perfect timing.

Then there’s the rest of us. The rest of us have succeeded because we were all raised, socialized, and helped by other people. Outside of academia, some of these people are obvious: parents, close relatives, coaches, and some teachers. But inside academia, not all of these people are as obvious. They might be that undergraduate professor who recommended we go to one grad school versus another, or the one who helped get us our first tenure-track job, helped lend a hand during a difficult time, or saved us from a desert island that one time by paddling through shark infested waters using only their right arm. With Thanksgiving coming up, it can be a nice chance to hit pause and think of 2-3 nonobvious people who might have done a small thing that made a big difference in your life. Doing something as simple as this can do your soul good. On one extreme, it reminds us that we aren’t the self-centered Master of our Universe as we might think when things are going great. On the other extreme, it reminds us that there are a lot of people silently cheering for us when we might think things aren’t going so great. What do you suppose would happen if you tracked these people down and game them a call? It’s four steps: 1. Find their phone number and dial. 2. “Hey, I’m ___; remember me? How are you?” 3. “It’s Thanksgiving. I was thinking of you” or "It's not Thanksgiving, but I've been thinking of you." 4. “Thanks” For about the past 30 years, I’ve tried to do this each Thanksgiving. It used to be the same 3-4 people (advisors and a post-college mentor), then a couple more, and this year I’m adding a new one. For some reason, I always look for an excuse why I shouldn’t make these calls. I always find myself pacing around before I make the first call. Part of me thinks I might be bore them, or they already know it, or it’s interrupting them, or that it’s too corny. Yet even if I have to leave voice messages, I’m always end up smiling when I get off the phone. I feel more thankful and centered. I feel happier. Maybe they feel differently too. Still, there’s some years I never made any calls, because I had good excuses. Maybe it was too late in the day, or they were probably with their family, or I called them last year, or I didn’t really have enough time to talk. I’m sure they had some good excuses – way back when – as to why they didn’t have time for me. I’m thankful they didn’t use them. If you can think of 2-3 people you’re thankful for who might not know it, you don’t have to wait until Thanksgiving next year to tell them. They won’t care that you’re a little bit late or a whole lot early. It’s only 4 steps.

0 Comments

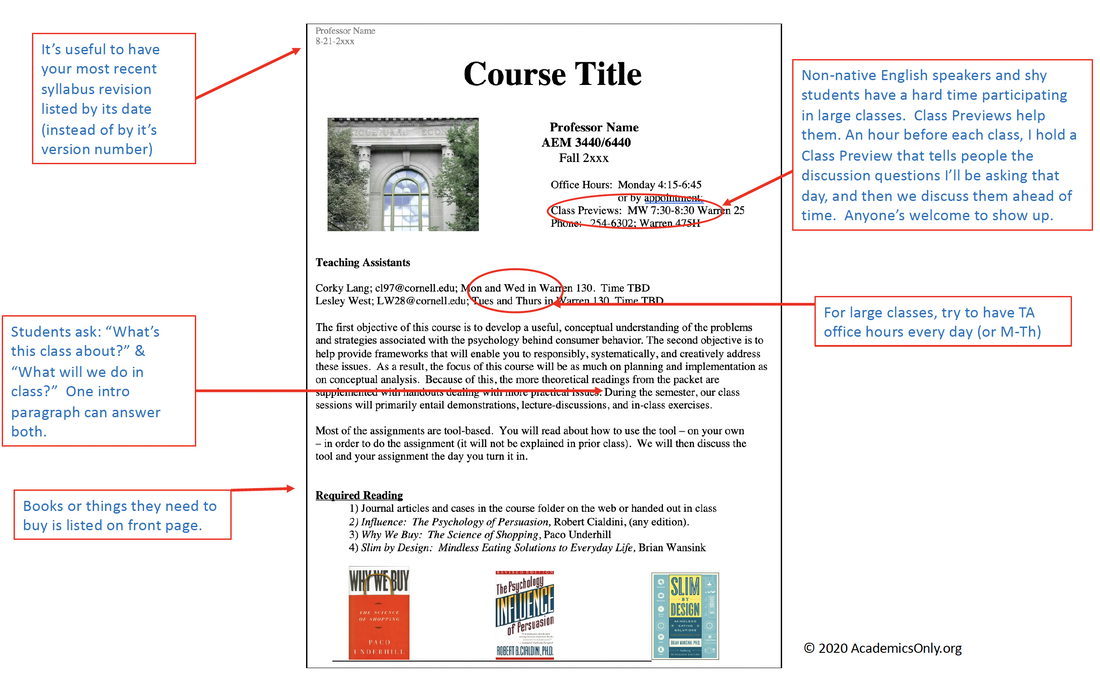

A close friend of mine believes successful PhD students have three things in common: They're smart, they work hard, and they have good judgment. The secret sauce here is "good judgment." Although smarts and hard work are important, most PhD students would have never been admitted if they weren't already smart, hard workers. But having good judgment is more elusive. It includes things like knowing what's "interesting" and what isn't, knowing what's worth worrying about (and what isn't), knowing what's important to prioritize, knowing how to solve a people problem, knowing whether to persist on a project or to move on, and so on. But advising a PhD student to "Have great judgment" is like advising a football team to "Score the most points." It doesn't tell them how. You can't say "Have great judgment" and then say "Next question," "QED," or drop the mic and walk out. Maybe there's two types of judgment -- technical judgments and nontechnical judgments. For graduate students, building technical judgment is about learning the whys of research. One way to build better technical judgment is to boldly ask lots of "Why?" questions of your mentor, advisor, or of an older student: "Why did you send it that journal? Why didn't you use a different method? Why did you ask the research question that way?" Most of us shied away from asking technical judgment questions because we didn't want to be irritating or look like we didn't belong. Most professors I know actually like to answer these questions, and they love to see an engaged student step out of a silent huddle. Developing good nontechnical judgment is trickier. Yet this is the critical judgment you need to troubleshoot how you can be a better teacher, or whether to choose the risky dissertation you want to do versus the safe dissertation your advisor wants. It involves figuring out how to deal with your off-the-chart stress level or whether you should take a job at a teaching college or go into industry. Our tendency as a graduate student is to get feedback from peers in our same year. A more effective one may be to get it from recent graduates or from professors who have seen cases like these and know how they worked out. You can even get nontechnical advice from professors you know in other departments. The best nontechnical dissertation advice I got was from a Medical School professor from my church. It was straightforward, unbiased, kind, and based on lots of students he had known. As professors, we can help to build better technical judgment by encouraging questions about our research judgment calls, or we can give it as color commentary or as context when we discuss a research project. But again, helping students with nontechnical judgments is trickier. One way to do this is in the third person. This can be by discussing a problem that "their friend" is having or by discussing a relatable case study. Here's one approach to building nontechnical judgment. I used to teach a PhD course where we'd meet in my home for a casual last class session. The first half of the session would be a discussion about graduate student success and the last half would be dinner. Each student had been asked to anonymously write down a dilemma that "one of their friends" was facing that was being a roadblock to their success. We'd mix these 9-10 dilemmas up, and we'd relax in the living room with a glass of wine and discuss them one at a time. For each one, we'd talk about similar experiences, options, solutions, and so forth. By dinner time, we had a more balanced perspective and some suggested next steps for many of the dilemmas. Over the years, it seemed that about 70% of these dilemmas were about the same 7-8 issues. These were like the issues mentioned above -- "risky vs. safe dissertation," "stress level," "leave academia," and so on.

Here's a second approach to building nontechnical judgment. Given how similar these dilemmas were from year to year, I wrote up 1-page PhD student case studies that involved slightly fictionalized people who were facing these common problems. These case studies were in the syllabus for the course, and we'd take the first or last part of each class to talk about that week's case study. The common dilemmas faced in your field may be different, but the enthusiasm your students would have in discussing them would probably be the same. Some people might be born with great judgment, but for the rest of us, it's a lot of trial and error and a lot of asking bold questions. If you're a graduate student, you've got a lot more license than you might think to learn from trial, error, and bold questions. If you're a professor, there's a lot we can do to help them. |

Welcome...Tips for PhDs is a how-to community that helps us share our best practices as PhD students, new professors, and independent scholars.

Helpful tools and tips on how to graduate, get tenure, teach better, publish more, and have a super rewarding career.

Relevant Posts

All

Some Older PostsArchives

April 2024

|

Share Your Insights and IdeasWhat have you created or found that's been useful and could be helpful for other PhD students, new professors, or independent scholars?

Send an email to [email protected] if you have something you think would be useful to share with others on this website, or if you have ideas on how to make this more useful to you or your students. |

Stay in touch |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed