|

Note: This is from an earlier 2018 blog post at BrianWansink.com Two years ago, I had no real idea what a "retracted" journal article was. I had never thought of it, or known anyone who had had one. If someone would have asked me, I would have probably said, "There must be something about it that was wrong."

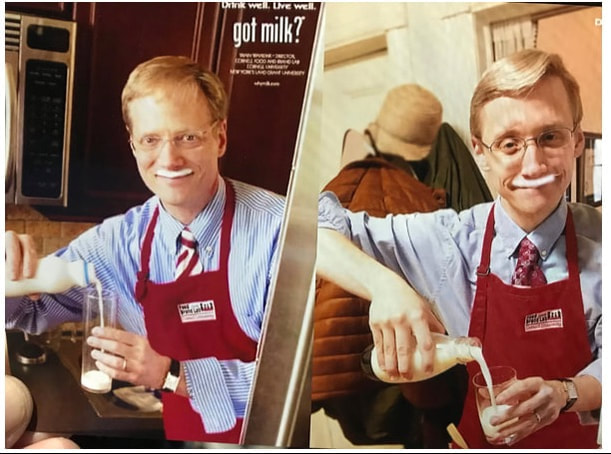

Two years later, I've had a some journals ask me to rerun analyses and to show original paper-and-pencil surveys from as far back as 2000. When we haven't been able to do so (didn't save the hard-copy surveys or can't track down the coauthor who did the analysis), some of the papers have been retracted because they can't be fully validated. Since then a few people have asked me if they can believe Article X or Y because they were retracted. I absolutely believe in these articles. The general conclusions are the same, and even if the original hard-copy surveys and original analyses done a number of years ago can't be found, new reanalyses (often done with different statisticians) generate similar conclusions. On Monday, one of my coauthors pointed out an insightful article that Dr. Stephen Holden had written for The Conversation website titled, "Retraction of a Journal Article Doesn't Make It's Findings False." One of his many points is that “Retractions may be important signals of reduced confidence in a finding, but they do not prove a finding false. This requires replication.” Social science moves forward because of replication and not rereanalyses. The Gold Standard of science is when independent researchers can run about the same study and come up with similar conclusions. This is why I wish I had published more detail in the method sections of some of my papers. Instead, when the editor said “Cut out 1000 words,” we cut it out of the methodology section or the references and stayed focused on the idea. Today, you can include all of the methodological detail and post on an online appendix if there isn’t room in the paper. Looking back, I’d also archive all of the analyses of my coauthors instead of assuming they’ll always have them on their computer or assuming they’ll never be needed. Coauthors can lose laptops, change computers, or leave academia. As for saving the original pencil-and-paper copy of surveys and coding sheets . . . do so if you have your own warehouse (the photo above was taken in 2005 in Illinois in what was supposed to be my garage). Otherwise you can collect it in a retrievable electronic form (if you think electronic collection won’t affect the results). Academics is an incredibly enriching calling. As you move forward in a happy career, I hope this is the only time you have to read about a retraction. Comments are closed.

|

Welcome...Tips for PhDs is a how-to community that helps us share our best practices as PhD students, new professors, and independent scholars.

Helpful tools and tips on how to graduate, get tenure, teach better, publish more, and have a super rewarding career.

Relevant Posts

All

Some Older PostsArchives

April 2024

|

Share Your Insights and IdeasWhat have you created or found that's been useful and could be helpful for other PhD students, new professors, or independent scholars?

Send an email to [email protected] if you have something you think would be useful to share with others on this website, or if you have ideas on how to make this more useful to you or your students. |

Stay in touch |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed