|

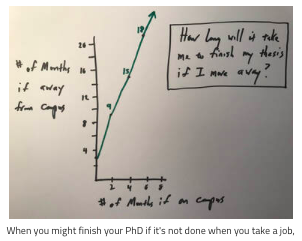

Some people love graduate school, but most of us want to finish it up and get started with our real lives. About a couple years ago I met a nice guy from Utah who was finishing his thesis at a university about 5 hours away. He had just moved here to take a job. After only two weeks, he was totally immersed in his new job, and I asked him if he was concerned about being able to finish up his thesis. He said, "Oh, no, not at all. My university's only 5 hours away, and I've only got a couple months of work left on it." The idea of starting a new life or a new job a few months early – say, before we’ve completed our dissertation – sounds pretty good. After all, lots of people Zoom and Skype from home, so it should be a snap to web-commute back to the university and finish up our dissertation away from the anxieties of campus. For instance, you could now start your new gig (maybe as a professor) in June instead of August. Your plan would be to move, get settled, wrap up the dissertation, and get two months of a tempting new salary. When I was a PhD student, someone told me that if you want to know how long it will take to finish your dissertation if you move away, you use a simple formula. You take your best guess of how long you think it will take to finish, then you triple it and add three months. So if you think you have 2 months left on your dissertation, and you move away in June, you won’t be finished until following March – in 9 months instead of 2 months (2 months x 3 + 3 months = 9 months). This is a rough rule-of-thumb, that varies across schools, departments, and people. Still, when I heard this, I wasn’t going to take any chances. My apartment lease with my two roommates was up, so I spent the last two months crashing at the apartments of different friends so I could wrap it my dissertation and graduate before I move away to start my Asst Prof gig.

What happens when you move is not only that it takes time to get resettled and you no longer have the support structure of your PhD program (and the “in sight & in mind” attention of your committee), but you also don’t feel the urgency to finish. You’re settling into a new role, and everybody's happy to have you around. You start to put off the uncomfortable pressure of you incomplete dissertation because it feels so much better to be treated as an an adult over here than as a sniffling child over there. But in a few months when your new department chair asks whether you’re through with your dissertation, it’s going to be awkward to answer. You might not have the option of completing a dissertation on campus, but if you can, it’s worth sleeping on couches until it’s done. ****************************************** The Rest of the Story: Four months after meeting the guy from Utah, I ran in to him again at the same boardgame cafe where we had originally met. He was very excited about having moved, and he was very excited about his new job. What's notable was that he never mentioned anything about his dissertation, how it was going, or whether it was finished. His dissertation had been an enthusiastic 80% of our conversation during the first time we met. Sine he never mentioned it, I wonder if he hadn't made the progress he had expected to make.

0 Comments

"Independent Scholars" are one of the three groups of people this website is designed to help. These scholars are people who may not be in a traditional research position, but they are people who still have a passion, or mission that drives them. Like this guy. He was a topic of a dinner conversation last week, and deserves to be a topic of a lot more dinner conversations. Successful people sometimes talk about their "Big Break." The moment that made the big difference in their life. What's rare, however, is to see to a successful person who mainly had "Bad Breaks." Meet the great Charles Henry Turner. Many discoveries about how insects communicate with each other and how they think come from the crazy-creative, shoe-string experiments and research papers of Turner. Born in 1967 -- right after the Civil War -- Turner was a standout zoology student at the University of Cincinnati and is thought to be the first African-American PhD graduate from the Univeristy of Chicago. Despite this and a strong early publication record, he was never able to find a University professorship and instead taught high school biology in St. Louis until passing away at 56. There's not any record of him complaining about being overlooked, passed over, or not having a Big Break. He was too busy. He kept his passion -- stayed the course of the mission he saw for himself. For 30 years he continued to think to ask out-of-the-box research questions -- like, can insects hear? -- and then design of ingenious experiments to test his ideas. He would then spend his nights and weekends collecting data and writing scientific papers that were published is some of the best journals in his field. Still, no university every hired him. No big break, mainly bad breaks. Still he didn't complain, he kept working, and he kept his "eyes on the prize." That seems to be his super power and why 100 years later he stands so tall above those hundreds of nearly forgotten others who were hired instead of him. There's an inspiring article on him in the Jan/Feb 2024 American Scientist. Great Charles Turner article (American Scientist Jan/Feb 2024) Download File

|

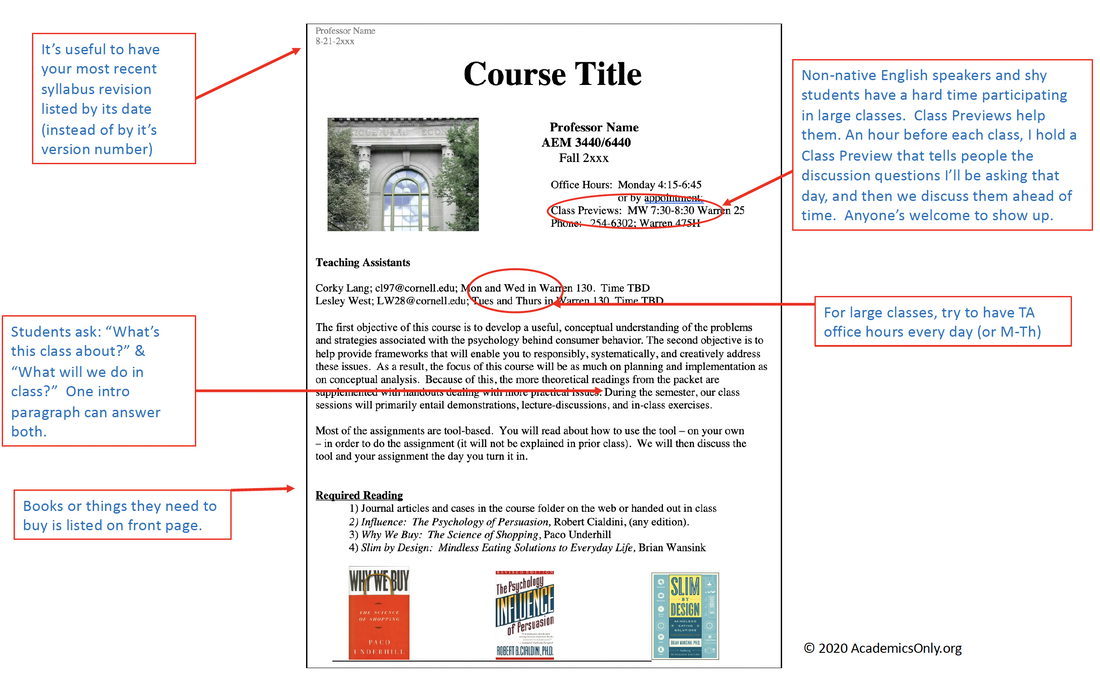

Welcome...Tips for PhDs is a how-to community that helps us share our best practices as PhD students, new professors, and independent scholars.

Helpful tools and tips on how to graduate, get tenure, teach better, publish more, and have a super rewarding career.

Relevant Posts

All

Some Older PostsArchives

April 2024

|

||||||

Share Your Insights and IdeasWhat have you created or found that's been useful and could be helpful for other PhD students, new professors, or independent scholars?

Send an email to [email protected] if you have something you think would be useful to share with others on this website, or if you have ideas on how to make this more useful to you or your students. |

Stay in touch |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed